Disappearing Snapchat Messages Complicate SHS Sex Abuse Investigation

By Patrick Malone | Follow the link to access the online article

SUMNER — As students prepared to return to Sumner High School last August, three teenage boys met at the Jimmy John’s sub shop to contemplate a bold decision.

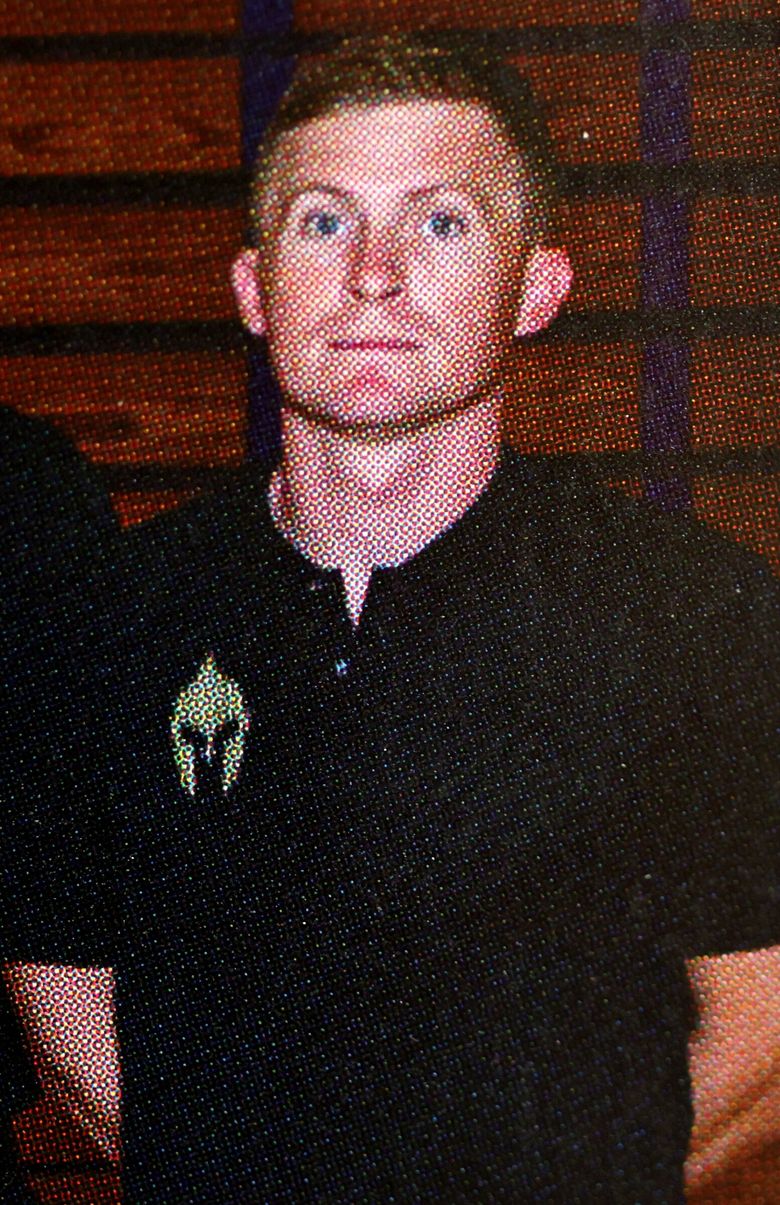

Together, they’d slowly realized that they had a dark experience in common: persistent requests from their basketball coach, Jacob “Jake” Jackson, to trade nude photos, according to allegations later reported to police.

Over sandwiches, two decided to talk with their parents, then, within days, a detective. Separately, four other teammates wrestled with the same dilemma before stepping forward.

Their statements triggered a scandal that would shock this town of 10,000 and engulf the popular young coach, regarded by many players and their parents as a conduit to college hoop dreams, in civil and criminal investigations.

Two players and their families sued Jackson and the athletic apparel firm that he married into, Sterling Athletics. Jackson, 35, has denied the allegations in court filings through his civil lawyers, Nicole Brodie Jackson and Jacob Roes. His criminal-defense lawyer, Brett Purtzer, declined interview requests on his behalf. Tacoma lawyer Bertha Fitzer, who represents Sterling Athletics, declined to comment.

Jackson was placed on leave and later resigned from the Sumner-Bonney Lake School District in October after a criminal investigation focused on him became public.

Six former players, ages 15 to 17, told Sumner police detectives that Jackson solicited nude pictures of them, and shared nudes of himself with them, according to interview summaries attached to seven search warrants obtained by The Seattle Times. The players say the abuse began when they entered high school. Two players said Jackson allegedly touched himself in their presence for sexual gratification. One player told investigators Jackson inappropriately touched him.

Police identified up to six more possible victims, according to court documents. Investigators say they’ve attempted to contact these possible victims, but none have come forward to file reports.

Seven months since the players first contacted police, the criminal investigation is still open. The Pierce County Prosecuting Attorney’s Office is waiting for the Sumner Police Department to present its findings, according to prosecutor’s spokesman Adam Faber.

A review of publicly available records shows the criminal investigation against Jackson faces headwinds.

According to search warrants, Jackson allegedly communicated with players via Snapchat, which enables users to send images that vanish after 10 seconds. Together, the players told police well over 100 photos were exchanged.

But Snap Inc., the app’s parent company, told detectives the images were irretrievable on its servers because of the settings Jackson and the players used. The texts that accompanied the images were turned over, although detectives wrote that they held little evidentiary value. The players themselves did not save any explicit photos to their phones, according to court records showing evidence gathered from a search warrant.

Further complicating the investigation, the Washington State Patrol crime lab faces significant delays in processing DNA evidence obtained in a search of Jackson’s home. There is no indication when it will wrap up.

Police have told Jackson’s accusers several times the conclusion of the investigation is near. “The date gets backed up — over and over and over again,” one accuser, identified in court records only as John Doe 1, told The Seattle Times. The newspaper does not typically name alleged victims of sex crimes.

Jackson isn’t allowed on school district property, except to pick up his kids at their elementary school, which is near the high school. That’s where John Doe 1 catches glimpses of his former coach, which leave him queasy, he says.

“Mind games” and “manipulation”

In Sumner’s charming downtown, diners do brisk business even on weekday mornings, drawing customers as they pass between an uninterrupted line of mom-and-pop businesses. The rare traffic jam can often be blamed on a freight train whistling across Main Street.

Above it all towers a two-story tall mural of Sumner High School’s mascot, a purple Spartan brandishing sword and shield, aptly representing the space prep athletics occupies in the town’s psyche.

The father of John Doe 1, who is not being named to protect his son’s identity, described an exchange he had with a Jackson supporter who believed the coach “was being railroaded.”

“There’s a lot of people in the community that believe Jackson is innocent,” said John Doe 1’s father. “And there’s a lot of people that think it was just text messages or something less serious than it actually was. It’s a small community. There are strong opinions, and it’s an uncomfortable topic, but the truth needs to be out there.”

Opinions in the small town are intense. The Sumner News Index published, then an hour later unpublished, a story about the filing of a second lawsuit against Jackson. “At this point I’d rather have this resolved in the criminal justice system and the courts than on Facebook,” wrote Publisher Mark Evers.

Back in 2016, hiring Jackson looked to be a feather in the Sumner basketball program’s cap.

Jackson was a high school teammate with NBA great Kevin Love at Lake Oswego High School in Oregon, the same prep program that launched former Washington State University star Klay Thompson. Jackson was also a graduate assistant under Hall of Fame coach Lute Olson at the University of Arizona.

“[Olson] taught you accountability and how to own up to your mistakes,” Jackson was quoted as saying in a 2020 story on SB Live, a prep sports website. “He taught you how to accept everyone for who they are. He taught you how to love everyone no matter their background or demographic. He taught you how to serve people without wanting anything in return.”

Before coming to Sumner, Jackson had success at Peninsula High School in Gig Harbor, including a 21-4 record and a sixth-place ranking with his final team. There are no public accusations against Jackson from his time at Peninsula.

In Sumner, he was known for his energetic style and devotion to players even outside the normal season. Players say he gave them expensive shoes and warehouse jobs in his father-in-law’s sports apparel company and hired them to work around his home on Lake Tapps.

At least two players earned college basketball scholarships, and the Sumner newspaper heralded his turnaround of the historically dismal program.

But long before the allegations surfaced last fall, the Sumner-Bonney Lake School District was aware of concerns about his behavior toward players, according to notes from Jackson’s 2018 performance evaluation obtained by The Times. An administrator raised “concerns that have come to my desk,” including “mind games,” “manipulation” and “individual text messages” to players.

The district also received an anonymous complaint to the Washington Interscholastic Activities Association in February 2020, sent by someone claiming to be a parent, which was also obtained by The Times.

“This Coach has personal contact [with players] in various forms constantly,” the anonymous complainant wrote. “Texts, phone calls, [direct messages] and Snapchat. From the time he began coaching and through today. And it isn’t just his players. We are talking with kids as young as sixth grade.”

School district spokesperson Elle Warmuth acknowledged the complaint “did raise a minor concern over the practice of personal communication such as texts with student-athletes.” She said district administration reaffirmed its expectations of Jackson, and “he did not have any issues with this.”

John Doe 1 told The Seattle Times that Jackson briefly deleted his social media accounts in response to the 2020 complaint, but soon resumed using them to send and solicit nude pictures.

The image that had blanketed Jackson since his arrival at Sumner began to unravel on Aug. 31 and Sept. 1, when the boys began talking with police.

“You’re the only one”

In interviews with Sumner police, the six players described remarkably similar experiences with Jackson. He befriended them on social media, they said, with innocuous conversations that started while they were still in middle school, as reported in a complaint to the WIAA, which then became sexual in high school, the players told police.

Jackson’s accusers told police that their coach was a constant, and increasingly inappropriate, presence on their phones. One boy showed police a trail of daily Snapchat messages from Jackson that stretched back more than 300 consecutive days. When players complied with his request for nude photos, they told police, Jackson would sometimes reply: “sexy,” “love you,” and told them, “You’re the only one.”

Some of the boys had been invited to Jackson’s sprawling home to ride watercraft on Lake Tapps. There, in Jackson’s walk-in closet that featured his extensive shoe collection, one boy says his coach masturbated in front of him. Another boy told detectives that on four occasions Jackson masturbated and touched the boy’s genitals as well in the closet.

On Sept. 21, soon after Jackson was placed on leave, Sumner parents flooded a School Board meeting. A video of the meeting, taken by one of the players’ parents, showed comments divided between parents worried that their children had been harmed, and others worried about disruption to the basketball team.

John Doe 1 said social media posts defending Jackson and questioning the truthfulness of his accusers initially bothered him. But months of therapy have helped him to set aside public opinion.

According to Warmuth, Jackson resigned Oct. 17, more than six weeks after police had made the school district aware of the allegations against him. On Oct. 20, the Sumner-Bonney Lake School District banned Jackson from all school district property, except the elementary school that his children attend, according to a letter from the district obtained by The Times.

“He used to be my role model,” John Doe 1 said. “I used to see the life he had — still involved with basketball, the house on the lake — as something I wanted for myself one day.”

He felt pressure to comply with Jackson’s repeated requests for photos because he “did not want to lose his employment opportunities with Sterling Athletics or jeopardize his playing time on the Sumner High School Boys’ basketball team,” according to his lawsuit.

That civil lawsuit is temporarily stayed, pending the criminal investigation.

Disappearing messages

The police search warrants sought evidence including the carpet from Jackson’s walk-in closet and his and his accusers’ Snapchat and Instagram communications. Police also obtained Jackson’s DNA.

Final steps of the investigation, however, have been mired in complexity and delay.

The State Patrol lab’s analysis of the carpet swath, to be analyzed for DNA from Jackson and one accuser, according to the search warrants, began in January, about a month after the Sumner Police Department submitted it, but is not yet complete, according to spokesperson Sgt. Chelsea Hodgson.

It is caught up in a significant backlog in processing sexual assault cases, a source of consternation across the state. The delays are caused by staff turnover, limited lab space and the complexity of cases, Hodgson said.

As of February, the lab had cut the backlog from 2,862 in December 2020 to 1,273. But because there is not a sexual assault kit to analyze, the Sumner case is in a queue of more than 730 similar cases.

A bigger hurdle is the apparent lack of a digital paper trail via the alleged Snapchat messages. According to investigative records, Jackson and his accusers configured their messages to disappear quickly. Snapchat’s servers “did not reveal any such photos,” according to a search warrant records.

“We are constantly exploring ways to make our platform even safer,” including technology aimed at detecting the sharing of sexual images with minors, a Snap Inc., spokesperson said in an email.

However, Snapchat did not directly answer why it continues to allow hard encryption of shared images that keeps them beyond the reach of law enforcement investigating sex crimes against children.

The Social Media Victims Law Center, a Seattle law firm focused on social media companies, has two pending lawsuits against Snap over irretrievable, deleted messages involving suspected drug dealers. One of their clients is a family from Renton.

“Snapchat’s disappearing message function facilitates criminal activity by providing criminals with a built-in mechanism to destroy evidence of their crime,” said Matthew Bergman, the firm’s founding attorney.

In Sumner’s two-detective investigative unit, a veteran detective who wrote the search warrants retired at the end of February. Sumner Deputy Police Chief Andy McCurdy, who is now leading the investigation, declined to talk about the specifics of the case.

“We have to follow the evidence where it takes us,” McCurdy said in an interview over Zoom. “Sometimes terrible things happen, and lack of evidence makes it impossible to prosecute.”

The ephemeral nature of certain social media evidence “makes it challenging for us as investigators…,” McCurdy said. “It doesn’t diminish the credibility of the person who reported it, but it does make it more difficult to corroborate what they said.”

And until the investigation is closed, a request to depose Jackson as part of the civil lawsuits, filed by Tacoma attorney Loren Cochran, is on hold, frustrating the players’ families.

“I know [police] are doing their job and it’s taking time to go through the mountain of evidence they have,” said John Doe 1’s father. “But the longer it goes, the more concerned I get that he won’t be held accountable.”